This is a tale of two Yales. First, a tame visit to the New Haven campus, and then an evening at the Yale Club of New York City that was anything but.

Last summer, while in Connecticut for a weekend trip with friends, I cajoled them into taking a detour to wander the storied streets of New Haven and the Yale campus. It was a quintessential East Coast afternoon: muggy, sweaty, sticky, miserable, and magic.

I struggled to keep my gaping mouth shut to flies as we took it all in. Ivy-covered walls, lush green quads laden with lounging students, foreboding stone buildings named after America’s most esteemed Robber Barons. Parts felt reminiscent of my own college campus—University of Michigan, majestic and ionic, historic and hopeful… like anyone can be anything on these grounds.

Anyone can be anything, but at Yale you need a student ID to get inside. My tour was mostly limited to building exteriors. We knocked on the door of the Skull and Bones tomb (no one answered); went to a bookstore and bought a mystery novel (Some Luck by Jane Smiley; I have yet to read); and enjoyed a blissfully cold, mint chocolate chip-flavored ice cream cone at a cute little parlor.

And then it was over. There was nothing else to do.

As we loaded back into our car and relished the air conditioned air, disappointment set in. That couldn’t be it. Where was the Logan Huntzberger type (Gilmore Girls boyfriend, the playboy son of a publishing magnate, and my first crush) to sweep me off my feet and debate the merits of Hunter S. Thompson? Where were the big adventures? What would I write about? I hadn’t met anyone. The list said “Go to Yale,” so maybe I should have taken that more literally: posted up in a coffee shop, snuck into a class, auditioned for the Whiffenpoofs. That’s what I’d missed. The original list probably actually meant for women to be students at Yale. Right?

Well…

The great irony of #27, “Go to Yale,” is that undergraduate women were not allowed to enroll at the college until 1969, eleven years after 129 Ways to Get a Husband was published in 1958. My best guess is the authors of the original list meant one of the following:

Go to Smith or Vassar or another college and bus to Yale. Before (and in the early days of co-ed), women from other colleges were imported for mixers. They were known as the “weekend women.”

Enroll in one of the graduate schools. In 1958, all Yale graduate schools except the Yale School of Forestry were open to women. That program was the last tree to fall—it went co-ed in 1966. Yale’s professional graduate schools had been co-ed since as early as 1869, when the Yale School Fine Arts first opened the door to women. Other programs took longer; in 1885, Yale Law School accidentally enrolled Alice Rufie Blake Jordan after she applied using only her initials. She graduated, but another woman did not walk through the doors of Yale Law until 1919.

Stand in the quad and look lost? No, really. From my research, seeing a woman on Yale’s campus who was not a professor’s wife was something of a marvel. In a 1968 article from the Harvard Crimson describing her three days at Yale during the now-infamous “Coeducation Week” (don’t worry, I’ll get there), author Jody Adams wrote:

One ecstatic sophomore stopped me in front of Sterling Library and told me that seeing a girl at Yale on a Monday was almost more than he could bear. After four years of prep school and two years of Yale he had been led to think that "girls folded and disappeared from Sunday evening to Friday morning."

Standing outside of Yale’s Sterling Library this past summer, I remember feeling dismayed I couldn’t go in and sniff a book. No ID card, no entrance. It never dawned on me that in 1958, a woman at Yale would have experienced the same closed door, except for an entirely different reason. In 2025, if I really wanted to take this list seriously, I could technically apply to Yale, register as a student, move to New Haven, and do the damn thing. The option exists. A little over 50 years ago, that was not the case.

I’m ashamed to admit that until my Yale adventure, I’d never really considered the work it took to get women on campus. Bad feminist, I suppose. Or maybe it’s the privilege of growing up in an era when women’s educational equality was never something I had to think about: Michigan had been coeducational since 1870 (Go Blue, am I right?).

Yale, on the other hand, was behind the times.

According to The Atlantic, in 1968 Yale had “only ever accepted men as undergrads, while some 75 percent of other American colleges and universities were coeducational. Yale was also one of only three Ivy League schools where women could not enroll at all in undergraduate classes: While Brown, Columbia, and Harvard, for example, were still technically male-only, students from their institutions’ adjacent women’s colleges—Pembroke, Barnard, and Radcliffe, respectively—could also take classes.”

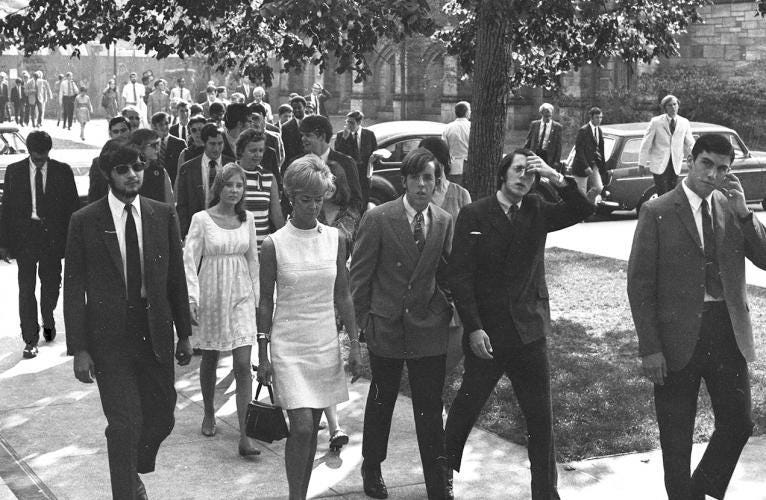

Coeducation was a hotly debated issue that came to a head during a student-sponsored Co-ed Week from November 4th - 8th, 1968. The idea was to invite women to campus for the week, open a dialogue, and host a debate. To quote Aviam Soifer ’69, one of the event’s organizers, “To make a valid decision about what women want in a coeducational school, it seems logical to talk to women about it.”

750 women from 22 colleges came down for the event. A little over a week later, Yale’s then President Kingman Brewster proposed a formal coeducation plan to faculty, who voted in favor 200 to 1 (you have to wonder who was the lone holdout?). When presenting his plan, he cited the coeducation week as “providing Yale with "uncommon excitement.""

The event was largely a success, a pressure point where everything shifted. But not all were friendly to the idea of women studying at Yale. The best account I found was the Harvard Crimson article by Jody Adams, who, at the time, was a Radcliffe student. The entire article is worth a read—entertaining and honest, Jody did not hold back. She attended a rally, chatted with visiting female students, lunched at Skull and Bones. In her three days on campus, she also wrangled a freelance piece for The Yale Daily News (okay hustler!). Her experience in the newsroom, not unlike her experience on campus, struck me:

There I was at Yale, for no reason except that a group of boys just couldn't stand it anymore, sitting in a strange newsroom, writing some story about some lady masturbating with a cross. It was bizarre and slightly absurd. All at once I was feeling isolated and quite lonely.

This was a theme.

In the fall of 1969, 250 freshmen and 250 upper-class women were welcomed to Yale. The New York Times reported “Yale Besieged by Female Applicants,” a headline that implies an enemy heading for the homefront. With coeducation, the first battle was won, but the war was far from over. Everything in the early days for women at Yale was a fight. Getting into classes, financial aid, basic safety.

The doors had been cracked, not swung wide, open.

Of course, I also didn’t think about this as I waltzed through the welcoming entry of the Yale Club of New York City on a snowy evening in February 2025. All I thought was, “Wow! Check out that crown molding!”

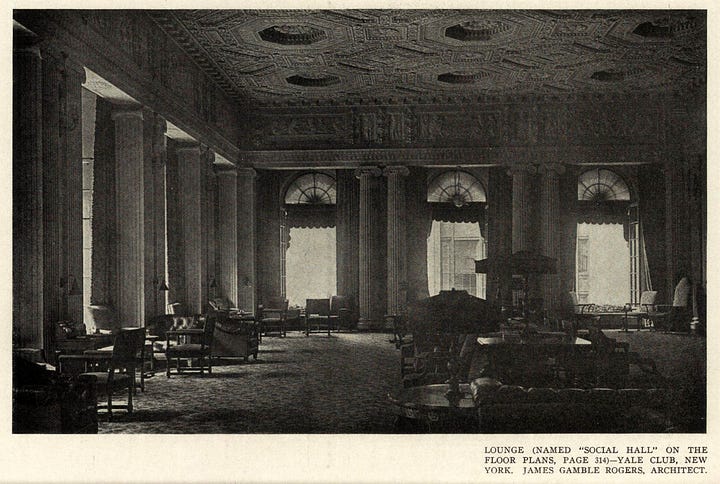

In the shadows of Grand Central Station, the Yale Club, located at 50 Vanderbilt Ave, is the largest college clubhouse ever built. Restricted almost entirely to Yale students and alumni, the 22-story club boasts everything from hotel rooms to a swimming pool to a rooftop bar. It’s an architectural marvel, ripped right from the Gilded Age.

As I took a step inside and shrugged off my coat, I gaped at the great foyer and the large staircase leading to the club upstairs. I was there for a drink with my old roommate Marina, her boyfriend Sam, and their friend Theodore. A graduate of the Yale School of Architecture, Sam had a membership and graciously offered to bring me. “For research.”

“Research” involved drinking one of the best martinis in Manhattan (bested, in my opinion, only by Bemelmans) in the Yale Club’s Main Lounge. This room not only felt but apparently is frozen in time (based on a photo I found from the archives, it has changed little).

Servers in suits wandered with silver trays, dispensing drinks and Cheez-its. A guest played hauntingly beautiful music on the grand piano in the corner. Folks chatted in respective groups, flitting between the nearby bar and whatever couch occupied their fancy. The walls were adorned with portraits of U.S. presidents who had gone to Yale. Quite the feeling, to be watched by Bill Clinton while sipping on Hendricks and olive juice.

This was #27. “Go to Yale,” Part Two, and I was eager for action. I scoped the room, practically swimming with khaki clad investment bankers. I’m not actually sure if they were all investment bankers. That’s an assumption—sue me. You can probably find a good lawyer at the Yale Club.

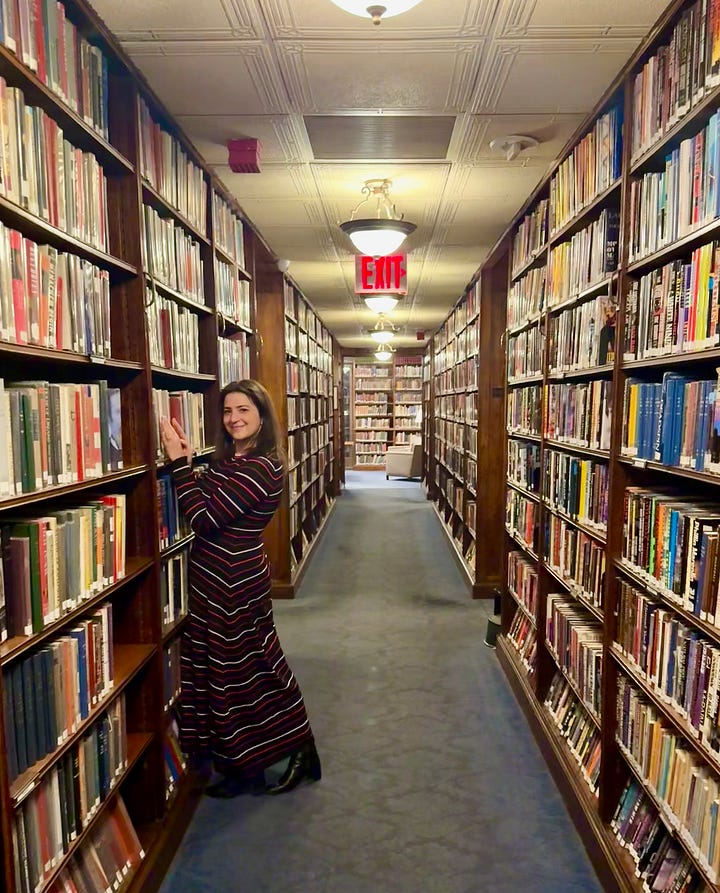

We went on a tour of the club. There was a section to watch the hockey game, a room for billiards, and a library. Oh, the library. I traced my fingers along shelf after shelf of books as we wandered the floor. Gorgeous wood desks, screaming for occupancy. A piano tucked in a corner. Utter silence. It was a place for learning. I could have stayed there all night.

But we made our way back to the Main Lounge.

“Who’s your favorite president?” Halfway to our couch, we were stopped by a man in a sport coat with a thick accent: The Irishman. He grinned at us, jerking his head toward the portraits. “You know, on the walls?” Marina slinked away as the Irishman and I locked in. My heart fluttered. The list had done it! A fun and flirty meet-cute within the confines of the Yale Club! Huzzah! The magic was almost too exciting to believe. He and I laughed, enjoying the moment, exchanged names, and shook hands.

And that’s when I saw it: a ring.

Back with the group, my head was spinning. He couldn’t be married. No way. Why so brazenly approach, flirt in the middle of the social club, friends watching left and right? It didn’t add up.

“Can I join you?” The Irishman returned, this time taking a seat on our couch. He joined our conversation with a purpose I couldn’t place. He mentioned a wife. He mentioned kids. He made intense eye contact. He left to watch the hockey game. What was happening?

And then once more, The Irishman returned as my friends and I prepared to leave. They peeled off, but I held my ground—I wanted answers. He sat across from me, settling into the plush armchair, and smiled. Cheez-it crumbs littered the floor, and a woman lazily plucked the piano in the corner.

“Are you married?” He balked as I looked at him expectantly. Here it was, that big twist, the explanation, it’s New York, there are all kinds of reasons why—

“Yes.” My heart sank. I was mad, or sad, or… I had so badly wanted to be wrong.

“Then what are you doing?”

He hung his head in shame, though whether it was from being called out or caught is anyone’s guess. “Honestly… I saw you from across the room, and I just wanted to talk to you.”

“And what did you think was going to happen?”

“I don’t know.” He plied me with effusive compliments, which though nice, felt tainted. “I don’t know.”

I could have told him that I was working my way through a list called “129 Ways to GET a Husband,” not “129 Ways to Meet Someone Else’s,” but instead I just stood up. Bill Clinton watched me as I left.

As my cab home sped over the Brooklyn Bridge, I ran the experience over and over in my head, waffling between what felt like a fun encounter and a deeper disappointment. I was bothered by it for obvious reasons, but there was something else I couldn’t place. I think it had to do with how the whole thing went down. The Irishman didn’t do anything technically wrong. He could have thought it was harmless flirting. But I didn’t, and I couldn’t shake that disturbing gut feeling.

I thought back to the first female Yalies and realized that the story—my feelings—rested on something bigger than being hit on by a married man at the Yale Club.

In 1969, the Yale women did not have it easy, but they must have had guts. Dubbed the female versions of Nietzsche’s “Ubermensch”—supermen— by a male student in an essay for The New York Times Magazine, the first female Yalies earned the moniker “superwomen.”

In many ways, they were. They fought tooth and nail for their education. The office of financial aid refused to offer resources to women, citing a commitment to the men first. There wasn’t even a gynecologist on campus until 1969. As far as all-male classes go, one professor was quoted in The Yale Daily News saying, “Until society makes its role assignments equal, I can’t help feeling a deeper satisfaction and sense of accomplishment teaching all-male classes. As a professor, I feel a greater sense of accomplishment when I direct my efforts toward those who will one day have a greater role in society—men.”

Sexism ran rampant: a common quote after coeducation was that Yale would now be producing “1000 male leaders and 250 wives.” In 1969, an informal survey of Yale women showed difficulty in establishing friendships with other women because there are so few of them, overcrowding and lack of privacy, and lack of dating. They resoundingly rejected the notion that they were there for an MRS. Degree, despite what many of their male peers implied.

The school was inhospitable to the women it worked so hard to admit. This is not surprising. For many, the motive behind coeducation had nothing to do with women. It “was based not on Yale’s seeing her mission as the education of both sexes, but on fears that Yale cannot continue to attract the nation’s top males to a non-coeducated campus,” according to Paul Taylor, a reporter for the Yale Daily News.

The women were brought on campus to appease the men. A revolution occurred instead.

Of course, the revolution that came in the 1970s was more than just Second Wave Feminism. It was the civil rights movement, Roe v. Wade, Vietnam, the Black Panther trial, all coming to a head while Yale attempted to create a coeducated campus coexistence.

In my research, I was struck by rhetoric from both supporters and opponents of the movement. The 50-some-year-old quotes sound eerily similar to conversations happening today both in favor of and against civil liberties, gender equity, and basic human rights. Reading archived articles advocating for diversity, equity, and inclusion at Yale in 1968, I’m struck by what’s going on in the present, as we watch institutions and corporations shirk and shutter programs designed to provide access.

It is a fascinating exploration, but this is a Substack post, not a senior thesis, so I have to wrap things up. I recommend the book Yale Needs Women, which goes into depth over this history and more. If you read it, let me know. We can start a book club.

When I started #27, “Go to Yale,” I thought I’d end up with a quippy anecdote about my love of Gilmore Girls or a semi-salacious story about an evening at the Yale Club. And the thing is, if I’d taken the list item at face value, I’d actually say it’s a pretty solid idea. College campuses, alumni clubs, and—if you went to Michigan—football bars are amazing places to meet someone with common interests, mutual friends, and similar experiences. Just make sure they’re not married if you hit it off.

But this is about more than just a good place to pick up a partner; the history of Yale’s coeducation is a reminder of why I started this project in the first place. Yes, to meet people. But also to look at what the world was like for women in 1958 and compare it to how we operate now. I shudder as I witness history repeating itself and those hard-earned rights being lost. I am moved and motivated, however, by the fight and the tenacity of these trailblazers—not just the Yalies, but every single woman who rejected the status quo and dared to question a different, more equitable reality. It feels very Socratic to end this with the question: How do we honor that? And what happens next?

I needed to see this today. We are Never giving up!

Who knew?? Love this...and damn that The Irishman